Medical

science has made incredible advances in our lifetimes — but one sobering

truth remains. "If you look at the death rate from cancer, there's no

dramatic change over the last five decades," says David Agus, author of The End of Illness and the head of University of Southern California's Westside Cancer Center. "There are little wins, but no dramatic change."

On the plus

side, the incidence rate of cancer has gone down somewhat, as fewer

people smoke and some obvious carcinogens have been eliminated from the

environment.

It's true

that we've learned a lot more about cancer in the past 50 years — but

mostly what we've learned is that cancer is a lot more complicated than

we thought.

"We truly

grossly underestimated the cleverness of cancer," says Ralph deVere

White, director of the U.C. Davis Cancer Center. We're sequencing the

genomes of many cancers, and what you discover is that "regrettably,

they have many more molecular changes than we ever saw."

Expand

Expand

Dr. White

adds that we've learned more about cancer in the past 10 years than we

had learned in the previous 2000 years. "Cancer never allowed us to get

so much information to address our inadequacy." And now, the challenge

is to "turn that data into knowledge," which requires a lot of

cutting-edge bioinformatics. (Too bad everybody's funding is being cut

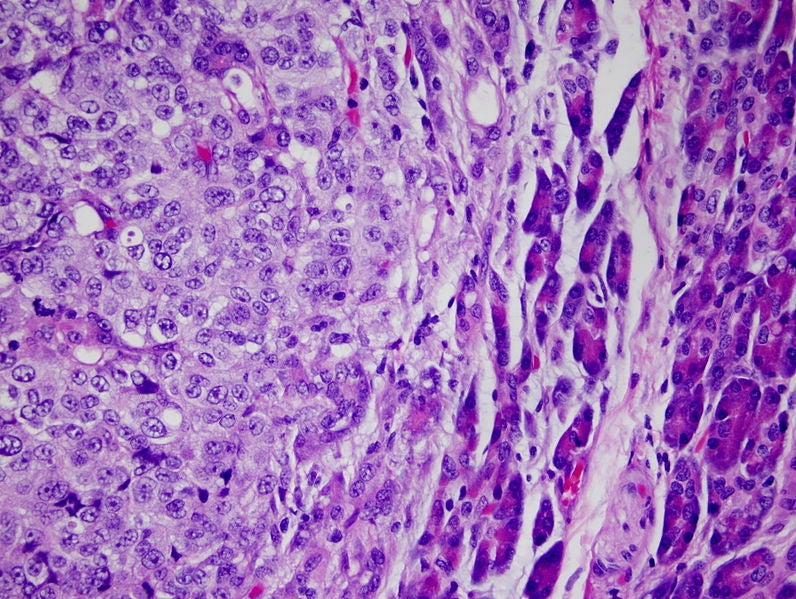

right now, at a crucial time in cancer research.) Melanoma image via National Cancer Institute.

You

probably already know that cancer is not just one disease — it's many

diseases, gathered under a single umbrella. But in the past, we thought

there were types of cancer called "breast cancer" or "prostate cancer,"

which were basically site specific — and now we've found that cancer is

much more varied.

"Cancer is

hundreds if not thousands of different diseases," says David Weinstock,

an assistant professor with the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute and Harvard

Medical School. "Saying, 'Why don't we have a cure to cancer,' is like

saying, 'Why don't we have a cure to infection.'"

There are

multiple levels of complexity, adds Weinstock: You have different basic

types, like colon cancer versus lymphoma. Then you have hundreds of

different types of lymphomas, and then every single person's lymphoma is

different at a molecular level. And even though you think of cancer

cells as all identical, in fact "not every cancer is the same, [and]

there are many differences within a tumor." When you attack a tumor,

"you're killing a diverse population" of cells, some of which will be

resistant.

Most cancers under treatment have 100 different mutations within a single tumor, says Agus. "It's very hard to model that."

Meanwhile,

you have to kill the tumor without killing the person who has it. People

talk about the "therapeutic index," says Weinstock — which is the

chances of killing the tumor, versus the chances of killing a normal

cell.

Another

wrinkle: cancer cells are bi-directional, meaning that stem cells can

differentiate into mature tumor cells — but mature tumor cells can also

turn back into stem cells, says Agus. Thus, treatments that have

involved just killing the stem cells in the hopes that this would keep

the cancer from recurring have failed, because the tumor can always

repopulate with more stem cells.

No comments:

Post a Comment