So yes, the

fact that we've been able to sequence the genomes of tumors has made us

realize they're much more complex than we ever knew. But we are also

slowly starting to develop more genetically targeted therapies – the

trouble is, so far these are only targeted at cancers that don't affect a

huge number of people.

Expand

Expand

According

to Weinstock, the Dana Farber Cancer Institute has a program called

"Profile," which involves looking for a list of commonly mutated genes,

to see if those genes are mutated in someone's specific cancer.

Eventually, he'd like to see more of the common mutations sequenced and

identified, so "we'll be able to say exactly what genes are defective in

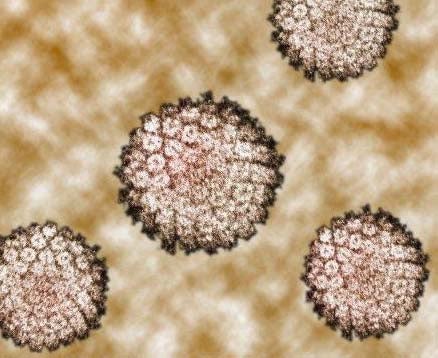

someone's tumor." Image via Andres Perez.

And once

you know what mutations someone has, you can probably figure out which

signaling pathways are affected by those mutations, and target those,

says Weinstock. For example, if you know someone has a problem with a

particular gene, you may know that you can use a specific type of

kinase-inhibitor on that patient, to block the enzymes that are

involved.

For

example, says White, we now have drugs that specifically address

mutations in the EGFR receptors. If you happen to have that specific

type of cancer and you take the drugs that block those receptors, "the

tumors just melt away." Also, there's herceptin for some breast cancers,

TKI inhibitors for renal cancer, or MDV3100 for prostate cancer.

"These

[drugs] are driven against molecular events," says White. There's also

been a shift in the mindset of drug companies, which used to prefer

cancer drugs that could be aimed at a wide swathe of patients, to sell

lots of drugs. Now, companies are learning that drugs that are very

specifically targeted at one relatively tiny population of cancer

patients can still make plenty of money.

"I would

anticipate the number of drugs we have 50 years from now will be

astronomically larger than today, and those drugs will be used in a much

more targeted fashion," says Sartor. Instead of a single treatment for

breast cancer, we'll differentiate it into "100 different types," each

with its own therapy.

"It wasn't

very long ago [that] Steve Jobs spent $60,000 having his cancer

sequenced," says White. But by next year, there will be a machine

available that will do the same thing for $1000 a pop.

No comments:

Post a Comment